Blog: Surrounded Android Game

- Jack Stevenson

- Sep 13, 2025

- 21 min read

Updated: Jan 10

Fall 2025

Surrounded: Postmortem

December 14, 2025

After 7 sprints spanning across 14 weeks, our game has finally been completed. Surrounded is now a finished game that anyone can play on the Google Play Store. To say that I'm happy with my team's work would be an understatement, as I am extremely proud of the game that we've been able to create together.

Now that my team and I have completed our mobile game, I think it's important that I reflect on my time working for TapTastic to make Surrounded. Reflecting on what we did right, what we did wrong, and what I've learned will let me take away valuable key lessons from this journey and apply them to future projects I work on.

In terms of what went right, I think we overall worked well as a team to produce this game. We all had a good work ethic and communicated frequently. However, there were 2 things I think we did exceedingly well in particular.

For our team, communication throughout development was very consistent. We always made sure to respond to one another quickly and be receptive to feedback. We also did a great job at maintaining a clear schedule that we followed throughout the 7 sprints. An example of our team's commitment to this was our in-person meetings hosted twice a week. Every Monday and Wednesday afternoon, we would meet at our school's library to discuss our game's state and develop it together. The 3 of us had a fantastic attendance record, with more than 90% of our meetings having all of us present. We also did well to inform one another when we had to skip a meeting. This frequent in-person routine helped us reinforce and support one another, as we were able to give much more immediate feedback and advice.

For myself, I wrote the majority of our game's code and systems neatly with proper commenting and formatting. I was able to adapt my code when needed and create new systems that strictly followed our game's design document. When I had time, I even added some of my own features and improvements to our game to really help it stand out. We can look to sprint 6 for an example of my work, where I dramatically improved the zombie animator system. During that sprint, I had some extra time on my hands after finishing work on the status handler system. With my team lead's permission, I rewrote our zombie animator system to be much more responsive to player actions and the world around them. This new system made it so that zombies could react to being damaged while also having more animation variety. Zombies could use 1 of 5 different attack animations when hitting a barricade or obstacle. The zombie's animations were also mirrored randomly, giving them even more variety.

In terms of what went wrong, a lot of our issues revolved around our game's scope and how we planned out development. While we were able to produce a high-quality game, these hurdles took time away from other features that we could have implemented or improved. Overall, there are 2 primary things in which my team and I could have done better.

For my team, our game's initial scope was too high for what we were able to accomplish. There were a few features we cut due to time constraints coupled with poor estimation for how long some things would take. As an example, my team and I were able to add 5 unique zombies to our game, each with their own stats and visuals. However, we had originally planned to add 3 other considerably more complex zombies to our game. This included a spitter zombie, a summoner zombie, and an exploder zombie. Each of these zombies would have had unique functionality that would have taken more time for all of us to implement. When our team's modeler and I realized how long these zombies would have taken to make, we talked with our producer and made the choice to scrap them in favor of more important systems. If we had planned for making the 5 zombies we were able to add, we could have saved time that was used to make models and code for cut enemies.

For myself, my largest blunder was with how I paced my development time. On some days I worked myself too hard and for too long. I would stay up far later into the night than what was healthy, compromising my energy levels the next day. While I thought staying up and overworking myself would lead to higher productivity, it ended up hampering productivity instead. As an example, I stayed up past 3:00 AM for multiple nights when creating our game's status effect system during sprint 5. Sleep deprivation from staying up late caused me to slow down the next day, hampering my productivity. If I had simply waited to continue development for the next day, I would have likely gotten more done over the sprint.

To wrap everything up, my team and I excelled in some areas but lagged behind in others. My team and I kept up great communication and routine, but we over-scoped our game and wasted time developing features that would inevitably be scrapped. I created a plethora of intuitive and in-depth systems for our game, but I paced my development schedule poorly and would occasionally neglect my personal needs.

Going forward, I've learned that it's crucial to keep scope in mind when developing a game. Prioritizing the most important features and saving the less necessary ones for later helps to ensure you don't have to be as worried about time constraints. I've also learned that pacing yourself is essential to maintaining energy and motivation. It's important to set a schedule, take breaks, and get rest to ensure you can maintain a good work ethic and stay healthy.

I'm really excited to see how I can apply these lessons to future projects that I work on. I can't wait to be able to contribute to more projects all while improving my own capabilities and developing connections with other developers.

Surrounded: Sprint 6

November 23, 2025

Sprint 6 was the last full sprint my team and I had to work on our game. Due to how Sprint 7 will only be 1 week, we had to cut some of our planned features and focus our efforts on polishing features already in our game. For this sprint, I improved the zombie animator, developed 2 new weapons, made an intuitive save/load system, and implemented systems for logging and updating persistent player data between games.

I started the sprint by working on improving the zombie animation system in our game. Prior to sprint 6, the zombie animator only made use of a single attack animation and had virtually no animation variation between zombies. Zombies would seemingly walk in unison due to a lack of animation variety, making them feel less interesting to fight. They also didn't react to player attacks beyond a visible red flash.

To give zombies more individuality when attacking something, I went into the zombie animation controller and converted the attack animation state into a blend tree filled with melee animations from Maximo. Each time the blend tree is reached, a custom state machine behavior randomly selects one of the animations to play. It also has another state machine behavior that has a 50% chance of mirroring the animation. Combined, these let zombies stand out from one another when attacking by making them use 1 of effectively 10 different animations (5 unique animations, each with a mirrored 'copy').

To make zombies react to being hit, I created a new additive animation layer that only affects the zombie's upper torso. The reaction works by having the zombie animator script call a trigger on the zombie's animation controller. This trigger plays a flinch animation on the masked additive layer, allowing it to flail the zombie's arms without interrupting walk or run animations.

Together, these changes make the zombies more interesting and responsive to fight against. It makes them feel less like perfect copies and gives them a bit more individual personality.

Next, I made a new weapons for the player to use against zombies: the Blizzard Shake. The Blizzard Shake, upon activation, freezes all zombies on the screen for 5 seconds. For 5 seconds after activation, it will continually apply a 10 second slow to new and existing zombies, emulating a short blizzard that impedes zombie movement.

The final system I worked on developing for the rest of the sprint was the save/load system. This took me a considerable amount of time to develop, as Unity doesn't have any built-in systems for saving and loading complex data structures. While Unity does come with the PlayerPrefs system, it's generally not recommended for more complex file/data types, as it isn't particularly safe from data loss. Instead, I had to make a custom saving and loading system using JSON files.

The save/load system works by trying to fetch a file in the game's persistent data path. If it exists, it will be used to create a player data class. If not, a new player data class is created with placeholder data for a new player. Other scripts are able to fetch and modify the player data class's value through a variety static scripts. When data should be saved, the player data class is serialized into a string and then saved to the disk as a JSON file. After testing, this system has proven to be very reliable and robust.

For my team's final sprint, I will be focusing my efforts towards refining existing elements of our game. I am going to integrate the leveling screen my teammate made, make perks with the existing parts system, and make some finishing touches where needed. I am really excited to see how our game comes out after months of work.

Surrounded: Sprint 5

November 9, 2025

For sprint 5, the work I completed was primarily on the back-end systems of our game. Specifically, I completely reworked our game's status effect system to be considerably more modular, efficient, and easy to adjust. Individual status effects can now apply multiple different effects, be either permanent or temporary, and have their effects be scaled by a potency parameter. While the meat of this sprint was spent overhauling this system, I also took the time to organize our project's files and complete a new weapon with unique functionality: the Sword Swipe.

Before I worked on the status effect overhaul, I wanted to fully reorganize our project's folder layout. I had already sorted my other team's project a few weeks prior and recognized that the benefits of keeping things tidy were worth the effort. While reformatting the file structure, I also started to implement Unreal Engine's recommended naming conventions. These combined helped to keep our file and folder structure neatly organized, accelerating our workflow.

Once I was done organizing the project, I turned my head towards the status effect system. Previously, the status effect system was considerably less robust or expandable. Status effects could only apply 1 effect at a time, status handlers had to recalculate each status effect every frame, and status effects could only be temporary. These limitations prevented me from developing some of the more intricate weapons we had planned for our game, thus warranting the system's overhaul.

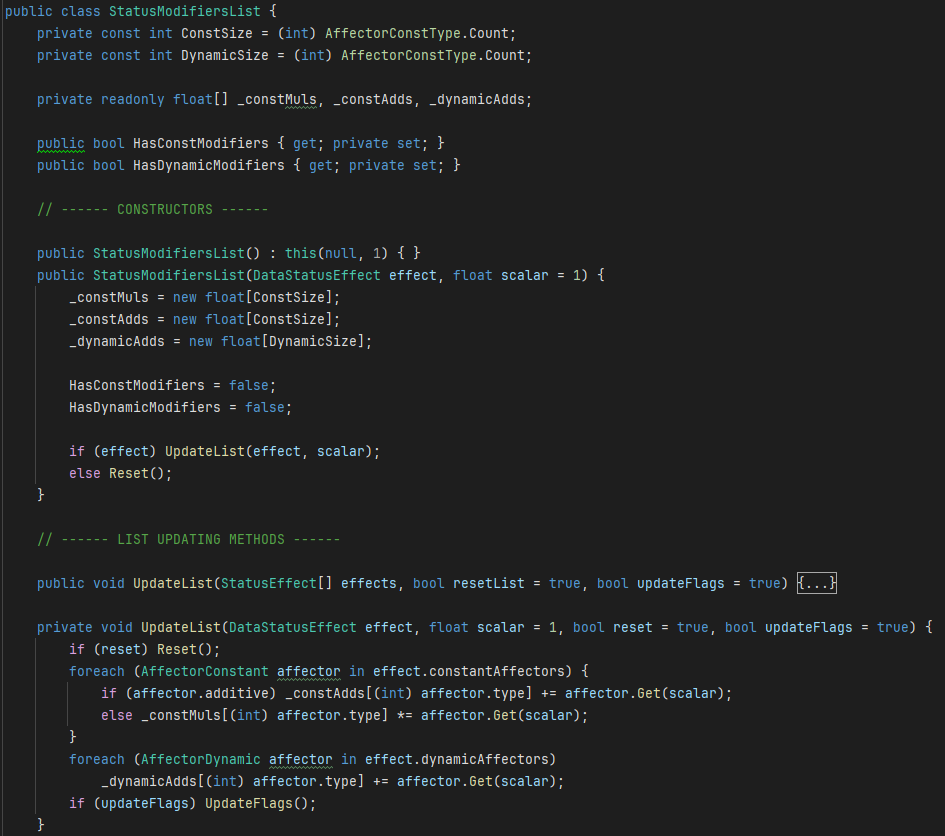

The first step I took to improve the status effect system was to make status effects able to affect more than 1 parameter at a time. I accomplished this by making status effects hold a list of affecter structs instead of a single effect type parameter and potency value. These affecter structs influence a single parameter each, allowing status effects to stack multiple affecters to influence multiple parameters at the same time.

Next, I status effects cache their modifiers into a single list upon creation. This optimization was import since my team and I are aiming for our game to feature large hordes of zombies at any given moment, each of whom could have one or more status effects at any given moment. Having a status effect's modifiers consolidated also makes it considerably easier to apply them to a character's corresponding parameter. These lists also have a plethora of functions to make their creation and application easier. They're even able to take a list of other status effects and compile each of their modifier lists into a master list of sorts, primarily for the status handler.

The final feature I implemented for the status effect system was the ability for status handlers to contain both temporary and permanent debuffs. While temporary debuffs are removed once their duration reaches 0, status effects in the permanent list are instead refreshed. This means that any status effect can be either temporary or permanent based on which list they're added to.

All of these changes made our game's status effects much easier to develop and tweak. With considerably more parameters to tweak and systems in place to automatically handle its complexity, I can easily churn out new weapons and abilities by using these status effects along with the parts system I've already made. Below are two weapons I was able to make with status effects and parts:

Blizzard Shake: Freezes all zombies for 5 seconds and continuously applies a 10 second slow to all zombies on the screen, new or preexisting.

Sword Swipe: Spawns a sword projectile that flies across a drawn path, damaging each zombie it hits.

Since my team and I are now in our final 4 weeks of development, I'll be focusing my efforts towards refining our game's existing systems as well as creating our final feature: the save system. This system will allow players to save and load their progress through JSON files stored in the game's persistent data path, allowing players to pick up and play right where they were from their last session.

Surrounded: Sprint 4

October 25, 2025

Sprint 4 marked the midpoint in Surrounded's 7-sprint development cycle. During the sprint, I developed two crucial features for player progression and gameplay variety: the perk system and the status effect system. I also implemented my teammate's loadout UI and the shake weapon. Near the end of the sprint, my team and I play tested our game with a large group, garnering valuable feedback we used to gauge progress and see what we should improve.

My first goal for this sprint was to finish the final weapon type: the shake weapon. It was the third and final weapon type our game was planned to have and it needed to be implemented before any other substantial features.

With the help of a teammate, we figured out how to use a mobile phone's seismometer to measure changes in the phone's current detected movement. When the phone rapidly changes movement directions (aka shaking), the input script will invoke an on-shake delegate. The weapon manager will then listen to this delegate and activate the player's current shake weapon on use. In testing, the shake was quite reliable and was even a favorite feature amongst play testers.

Moving on, our teacher required our game to have roguelike elements from the very beginning. In other words, our game needed meaningful progression between 'rounds' of gameplay. To satisfy this requirement, my team's designer drafted a collectable perk system in an earlier sprint where players can earn a variety of perks through gameplay. These perks will drop as individual instances with slightly randomized stat values and a rare chance to come with an additional, unique benefit.

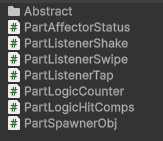

To create this perk system, I had to consider how I want perks to interface with weapons and the poor soul. After some thought, I came up with an intuitive parts system that will be used to create perks and unique weapons.

This parts system works by chaining components together to create simple logic chains. Each part has a dedicated function (counting, spawning objects, listening to weapon inputs, etc) and can communicate with other parts through Unity Events. Parts can also have criteria lists that require referenced parts in the list to be 'activated' in order for the observing part to be invokable. This modular system lets me quickly create weapons perks through dragging and dropping components into a the scene. Perk randomization and loot systems will come in a later sprint.

After developing the parts system, I went to work developing the status effect system. This system would be reliable for handling all status effects that zombies and the poor soul will be afflicted with. It needed to be robust enough to support a variety of different status effect types and allow for the easy creation of new status effects.

The system I ended up developing works by storing a zombie's current status effects in a list of status effect structs. Status effects can be added to this list and will be processed in the fixed update loop. This status effect handler will then accumulate the speed/damage/resistance modifiers of each currently active status effect and store them in public variables for other scripts to reference. The structs also have an internal timer, allowing them to eventually expire and incrementally apply damage if the status effect is a damage over time effect.

The last thing I implemented was a loadout screen for the player. This loadout screen was designed by one of my teammates, meaning all I had to do was simply program its logic. It works by keeping track of each weapon and perk the player currently has equipped. Once start game button is pressed, these equipped weapon and perk references are set to persist upon scene change and then be added to the player's weapon/perk managers. The loadout also has a crude 'leveling' system that unlocks weapons based on the furthest wave you've started. Combined with the rest of the game, the loadout screen gave the player much more control over how they played the game and gave incentive for the player to keep playing after finishing a run.

With these systems fully implemented into the game, we were ready to have players test our game. The feedback from these testers was very positive, as many players spent a couple of minutes engrossed in our prototype. We also collected plenty of criticisms for our game, with most being about a lack of responsiveness from tap and shake attacks.

During our next sprint, my team and I will continue to refine our game's core features. We will design more art assets, weapon types, and visual effects to ensure our game has plenty of content and feels responsive during combat. I'm personally going to be implementing a more intricate leveling/perk earning system that will reward players for prolonged play. Personally, I'm very happy to see how far our game has come.

Surrounded: Sprint 3

October 12, 2025

For our third sprint working on Surrounded, I spent the first half of it developing the required features for our game to be properly tested. I had to implement the poor soul, barricades, tap weapon, zombie logic, UI, and main menu. We then took the time to playtest our game with a plethora of testers, gathering feedback. For the rest of the sprint, I worked on the zombie visuals and the swipe weapon type.

Implementing the barricades and poor soul was fairly straightforward. I already created a damageable class that zombies inherit from, giving them health, the ability to be damaged, and an on-death delegate. For the barricades, I just gave them a damageable component directly and gave the barricade gameObject a ‘Barricade’ tag. For the poor soul, I made its custom script inherit from the damageable class and made the game manager script open a game over window once the poor soul died.

While the player could already tap and kill zombies, its logic was hardcoded into the weapon manager script. To allow for different weapon types, I made a base weapon class with a plethora of parameters and abstract functions that other weapon types would inherit from. This allowed the weapon manager to interface with different weapon types through the abstract functions the weapon classes would override.

After the boilerplate code was done, I then created the tap weapon. It works by performing a sphere overlap check wherever the player clicks and damages all zombies found in that area. The tap weapon also makes use of the base weapon class's damage, range, penetration, and energy.

The last main feature I worked on before the playtest was an enhanced zombie AI. Originally, zombies were uninteresting to engage with. They would take the shortest path to the player and just stand there idly. To remedy this, I created a logic state system to help reduce how repetitive zombies seemed to be and break up their pathing a bit.

This new system I developed has 4 states that the zombie alternates between based on its current situation:

Approaching: Moves the zombie towards a pre-selected approach point 2.5 units away from the player. This alone really helps to prevent hordes of zombies grouping up on a single point.

Charging: Moves the zombie directly towards poor soul once it's close enough to either the approach point or poor soul.

Attacking Side Target: Continually checks space in front of the zombie. Stops zombie to attack obstacle if it has a damageable component.

Attacking Main Target: Makes zombie attack main target (poor soul) when close enough.

These 4 states helped to make zombies more dynamic and seemingly individualistic, rather than it feeling as if they’re just following a path.

I then quickly implemented my teammate’s UI and Main Menu scenes into the project after I was done with the zombie AI. Once we had the UI and general gameplay loop in, we submitted our build for playtesting.

From our playtesting, we learned that players enjoyed the feeling of tapping to kill zombies. Players liked when the game became more intense and they had to put in more effort to keep the zombies at bay. However, a few players talked about how the game got boring after a short time. They talked about how it felt repetitive without any meaningful changes in the core gameplay loop. Some other players also mentioned that the tapping felt inconsistent.

With these critiques, my team and I got to work improving our game. My teammates primarily worked on updating the game design document and the game’s art. I put my effort towards making a swipe weapon type and adding animations.

The swipe weapon was much more complicated than the tap weapon, primarily because its hitbox is supposed to be a path the player made while swiping. To do this, I made a custom physics function that performed a capsule cast between each line segment of the path. Each zombie found would then be added to a list and have their colliders disabled temporarily. Once all path segments were tested, the zombie colliders were re-enabled and all hit zombies were damaged. Since the weapon doesn't need to worry about hitting zombies with disabled colliders, it doesn't need to preemptively filter through the zombies found between each line segment to avoid duplicate entries. This helped tremendously with both performance and simplicity. The swipe attack also ended up feeling really good.

Finally, I also improved the zombie visual script and animator to make zombies look much smoother. For the script, I made it smoothly interpolate the moveSpeed parameter on the animator instead of immediately setting it to eliminate snapping when the zombie came to a stop. For the animator, I increased the transition duration from the attacking state to the idle state so that the arms would reach the idle pose more gradually. Finally, I added an additional transition state between the attacking and movement states which triggered once moveSpeed was above 0 to prevent the zombie from 'sliding' after they break a barricade.

For my next sprint, I'll be working on making the shake weapon and start adding perks to the game. Perks will be gained from lootboxes that you can earn by completing milestones. These perks will allow the player to do build-crafting with their loadouts, greatly increasing replayability.

Surrounded: Sprint 2

September 27, 2025

During our second sprint working on Surrounded, the work my team and I did fixated around establishing a minimum viable game. We had to work around the clock to get a working prototype done so that we could start playtesting our game's features during the next sprint. For me, this meant establishing many of the game's core components that would be enhanced and adjusted according to the feedback we would receive from playtesting.

To start, I made a rudimentary class map for all of the scripts we would need for this game. This map shows how each class should communicate with one another, as well as which scripts should be observed by other scripts. I also created the boilerplate code for the manager scripts in Unity so that integration across systems would be easier. For the rest of the two-week sprint, I focused on developing the 3 most important systems so that we could playtest once combined into a prototype: the game/wave managers, the input manager, and the weapons manager.

The first system I focused on was the game/wave managers. This system was essential for our game, as it directly controlled the game's state and how zombies would spawn based on the current wave number. I had originally created a simple spawning system in the zombie manager script for testing, but this needed to be moved entirely to the wave manager, as the zombie manager's only job is to manage a pool of active and inactive zombies in a central place for improved performance.

We wanted the game's waves to feel similar to Plants vs Zombies, where each wave had 2 elements to it: zombie trickle and zombie hordes. The zombie trickle spawns in zombies at a set frequency over the course of the wave. Similarly to Plants vs Zombies, the trickle frequency should start to scale up as you play through more difficult levels (or in our case waves) to challenge the player as they progress. The zombie hordes spawn in massive groups of zombies all at once, typically at the end of a level/wave. The size of these hordes should scale with level/wave number, and multiple hordes should also be able to spawn when waves get long enough.

After the game/wave system was done, I went to work developing the input system. Since we were targeting mobile platforms, I had to make sure our game could properly handle touch, swipe, and shaking inputs that could be interpreted by the player's active weapon. I accomplished this by making a central input script that would invoke delegates through methods called by a Player Input component. I chose to base this script on Unity's newer input system since it gives much more control over how the engine interprets inputs. It makes the creation and modification of input bindings much easier than if I had to hardcode everything myself.

With an input system in place, I finally started chipping away at the weapons system. I needed this system to be very modular, as I wanted to use weapons system to create a variety of the weapons we planned for the game. Some of these planned weapons included poking attacks, swiping attacks, phone shaking attacks, and placed traps. To accommodate for this large variety of weapons, I made an abstract weapon class that weapon types could inherit from. This meant that all weapon types could be managed by a single weapon manager script while still allowing for unique functionality. I was able to get a basic tap-based weapon type working super quickly, proving to me how versatile the system was.

Combining all of these systems left us with a working prototype that we could now playtest with volunteers. I also made sure to get a build working on my android device so that playtesters would have a much more accurate experience beyond Unity's simulator. The data we'll collect will then be used to tweak the systems we have currently implemented, allowing us to tune our game in line with our target audience.

For our next sprint, I will be focusing on designing more of the weapon types that we want for our game. I will also create a feedback form for playtesters to fill out once they're done. With this form, I'll then find multiple people to playtest my game and use the feedback they give to iterate currently implemented systems.

Surrounded: Sprint 1

September 13, 2025

Surrounded started out as a simple idea that a friend ran by me for a game. group of friends and I decided to create and publish mobile game to the Android store with. To do this properly, we were expected to create a fleshed-out treatment, make a Trello board filled with cards and epics, set up a Unity project and show our progress to the class at the end of each sprint.

Similarly to my 470 class, I first had to pitch in front of my class. This had to be a pitch for a game concept of my own, as everyone was required to pitch an idea. I made a Payday 2 inspired top-down stealth game with inter-game progression systems. While I am proud of the pitch, I wanted to be a programmer rather than a producer. I also had to pitch my own experience as a developer so that I could let any possible teammates know about my capabilities as a developer.

I ended up pairing up with two people, one of whom I had previously worked with on our CAGD 377 Resident Evil 7 Recreation. Him and his friend would be the game designer and producer respectively, but they would also take on modeling, texturing, and UI development while I tackle programming. We called our group TapTastic.

Our game was a top-down horde-based tapping game called Surrounded. In Surrounded, you must protect a lone survivor as zombies pour into the room he's bunkered down in. Zombies can be slain by tapping them with a variety of unlockable weapons and upgrades, as well as guns that the survivor can use.

Once our team was situated, I started to get to work on the GitHub repo with the Unity project. I made sure to lower the Unity project's graphical settings, since we are going to be targeting lower-end hardware. Since we also wanted our game to be more pixelated, I lowered the camera's render scale to get a more pixelated look. This would also help our game run even better, as we were planning on having a lot of zombies on the screen at any given moment.

After the Unity project was set up and shared to my teammates, I started work on implementing the zombies. As I said, we wanted there to be a lot of zombies on screen at any given moment. This meant that, in order for our game to run well on lower-end hardware, we needed a way to efficiently handle large hordes of zombies without incurring a performance hit. Before the optimizations, I implemented a zombie class that inherits parameters (health, visuals, speed, etc.) from a scriptable object that will be assigned to it. I also gave the zombies a nav mesh agent so that they're able to walk around walls in more complex labels. They won't be allowed to path find around destructible objects, though, to ensure said objects have more of an impact.

After I got the base zombie class working, I made a zombie manager and pooling system to control all of the zombies. This system was designed to be robust and easy to modify/add to, so that we can implement more features without having to rewrite a lot of code.

One of the zombie manager's main features is that it calls custom update/fixed update methods for the zombies each update/fixed update. Unity's update and fixed update functions have a small overhead on their own, which starts to add up when more objects with update or fixed update loops are created. Having the manager update the zombies through a single update loop instead negates this overhead entirely, allowing for more zombies on screen at once.

As a team, our first sprint together went really well. Even though there were some mild hiccups here and there, I'm happy with the work that we've been able to produce and show to the rest of the class. For our next sprint, I will be working on the weapon system and the ability to kill zombies through taps. This can then be expanded upon through upgrades and other systems that we will add in future sprints.